An app that lets you record your phone conversations and pays you for the audio—so it can sell the recordings to AI firms—has, surprisingly, climbed to the No. 2 spot in the Social Networking category of Apple’s U.S. App Store.

Neon Mobile presents itself as a way to earn money, promising users “hundreds or even thousands of dollars per year” in exchange for access to their voice calls.

According to Neon’s website, users receive 30¢ for every minute spent calling other Neon users, with a daily cap of $30 for calls to anyone else. There are also referral rewards. Appfigures data shows Neon was ranked 476th in Social Networking on the U.S. App Store on September 18, but by the end of yesterday, it had surged to 10th place.

By Wednesday, Neon had reached the No. 2 spot among free social apps on the iPhone.

Earlier that same morning, Neon also became the seventh most popular app or game overall, and later moved up to sixth place among all apps.

Neon’s terms of service state that the app can record both incoming and outgoing calls. However, the company’s marketing materials claim that only your side of the conversation is recorded, unless you’re speaking with another Neon user.

Neon’s terms specify that the collected data is sold to “AI companies” to help “develop, train, test, and improve machine learning models, artificial intelligence tools and systems, and related technologies.”

Image Credits:Neon Mobile

Image Credits:Neon Mobile

The existence and approval of such an app on major app stores highlights the extent to which AI has infiltrated personal spaces once considered private. Its high ranking in the App Store suggests that a segment of users is now willing to trade their privacy for small financial rewards, regardless of the broader implications.

Despite the privacy policy, Neon’s terms grant the company a sweeping license over user data, stating:

…a global, exclusive, non-revocable, transferable, royalty-free, fully paid license (including the right to sublicense at multiple levels) to sell, use, host, store, transfer, publicly display, publicly perform (including via digital audio transmission), communicate to the public, reproduce, modify for display purposes, create derivative works as permitted in these Terms, and distribute your Recordings, in whole or in part, across any media formats and channels, whether currently known or developed in the future.

This broad language gives Neon significant flexibility to use user data in ways that may go beyond what is advertised.

The terms also mention beta features, which come with no guarantees and may be unstable or buggy.

Image Credits:Neon (screenshot)

Image Credits:Neon (screenshot)

Although Neon’s app raises several concerns, it appears to be operating within legal boundaries.

“Recording just one side of a call is designed to avoid violating wiretap laws,” explains Jennifer Daniels, a partner at Blank Rome’s Privacy, Security & Data Protection Group, in an interview with TechCrunch.

“In many states, both parties must consent to a conversation being recorded… It’s an interesting workaround,” Daniels adds.

Peter Jackson, a cybersecurity and privacy lawyer at Greenberg Glusker, agrees. He tells TechCrunch that the mention of “one-sided transcripts” could be a way for Neon to record entire calls but only include the user’s side in the final transcript.

Legal experts also raised questions about how effectively the data is anonymized.

Neon says it strips out names, emails, and phone numbers before selling data to AI firms, but doesn’t clarify how buyers might use the information. Voice data could be exploited to create fraudulent calls that mimic your voice, or AI companies could use your voice to develop synthetic voices.

“Once your voice is out there, it could be misused for scams,” warns Jackson. “This company now has your phone number and enough information—recordings of your voice—to potentially impersonate you and commit various types of fraud.”

Even if Neon itself is trustworthy, the company does not reveal who its partners are or what those partners might do with user data in the future. Like any company holding valuable information, Neon is also at risk of data breaches.

Image Credits:Neon Mobile

Image Credits:Neon Mobile

During a brief test by TechCrunch, Neon did not notify users that calls were being recorded, nor did it alert the person on the other end. The app functioned like any standard VoIP service, displaying the caller’s number as usual. (Security researchers may want to further investigate the app’s other claims.)

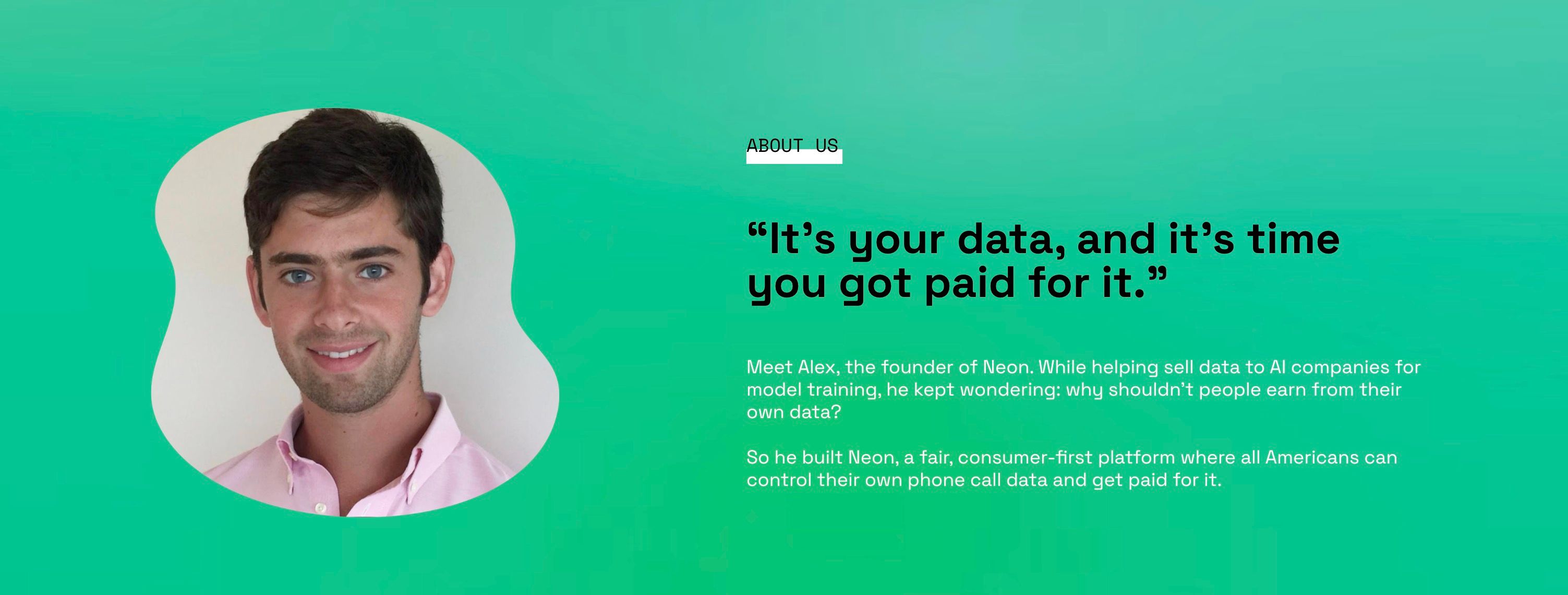

Neon’s founder, Alex Kiam, did not respond to a request for comment.

Kiam, listed only as “Alex” on the company’s website, reportedly runs Neon from an apartment in New York, according to business records.

A LinkedIn update suggests Kiam secured funding from Upfront Ventures for his startup a few months ago, but the investor had not replied to TechCrunch’s inquiry at the time of publication.

Has AI made users less sensitive to privacy issues?

There was a period when companies seeking to profit from mobile app data collection did so discreetly.

Back in 2019, when it emerged that Facebook was paying teenagers to install a surveillance app, it caused a public outcry. The following year, it was revealed that app analytics firms were running dozens of seemingly harmless apps to gather data about the mobile ecosystem. Users are frequently cautioned about VPN apps, which may not be as private as they claim. Government reports have also documented agencies purchasing “commercially available” personal data on the open market.

Today, AI-powered assistants routinely join meetings to take notes, and always-listening AI devices are widely available. But in those scenarios, everyone involved is aware and has agreed to being recorded, Daniels tells TechCrunch.

Given how common it is for personal data to be collected and sold, some people may now feel resigned to the idea and decide they might as well get paid for it.

Unfortunately, they may be sharing more than they realize and could be compromising the privacy of others in the process.

“There’s a strong desire—among knowledge workers and really everyone—to make work as efficient as possible,” says Jackson. “Some productivity tools achieve this at the expense of your privacy, and increasingly, the privacy of those you interact with daily.”